Here is a chart showing the track of the five named storms so far this year.

Andrea went from 5Jun-7Jun, She got to 63mph with a pressure of 992mb.

Barry went from 17Jun-21Jun, winds between 51-52 mph and a pressure of 1003mb.

Chantal went from 8Jul-10Jul, winds of 63mph pressure of 1005mb.

Dorian went from 24Jul-3Aug, winds got to 57 mph and a pressure of 999mb.

Erin went from15Aug-18Aug, her winds got to 40 mph with a pressure of 1006mb.

Why has the season acted the way it has?

This season we've seen a lot of wind shear. Also the SST was only marginal for supporting tropical cyclones. But the main reason has been the air in the Central Atlantic has been unusually dry this season. Many are throwing in the towel on the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season. Saying if the tropics don't heat up soon, the season is over. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Climatology speaking we're only getting into the peak Atlantic tropical season. The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1st through November 30th. ( Originally the season went from June 15 -October 31. Over the years the start shifted to June 1st and prior to 1965 the end date was November 15. ). Peak season is from August - October.

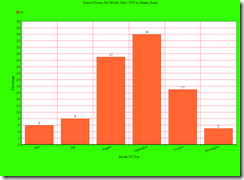

Here are a few Charts I made up. Source is the NHC data archive.

The above chart shows how the numbers breakdown for named storms during Hurricane Season in

the Atlantic Basin.

The chart above shows that vast number of named storms develop Aug -Oct.

The above chart shows that 84% of Hurricanes form during peak season.

The above chart shows the vast majority of major hurricanes occur during peak season.

A major hurricane is one that has at least sustained winds of 111 mph.

Peak season is when tropical cyclone killing vertical wind shear is at its lowest. It's also the time when generally instability is at its greatest. It takes the waters of the Atlantic a few months for the SST to warm enough and deep enough to really be able to support tropical cyclones. Aug 10 is the average date for the first Atlantic hurricane, according to this data.

Today there are no tropical cyclones out there in the Atlantic Basin... Just a little blob in the Caribbean that the National Hurricane Center (NHC) is giving a 10% chance for more tropical development. This is what's left of the tropical wave that went through the Keys on Wednesday. As of this writing the upper level low does look like it wants to organize, so we will see. But of more importance is the fact that the Tropical Waves over Africa are getting stronger.

Things can change very quickly in the tropics. So give it some time and it may get there. With that huge ridge of high pressure All it takes is for one tropical cyclone to stay alive and reach the Western Hemisphere , and it's game on.

looking back at past seasons.

There have been several tropical seasons that started off slow. In 1992 no storms formed until late August. Another year that had a slow start was 1954. In 1954 Carol was the first hurricane to form. She developed from a tropical wave near the Bahamas on August 25th. The 1954 hurricane season was a bad one for the East Coast/Northeast. If you want to read about the 1954 season here's a link.

Just because the season is half over, doesn't mean the Northeast is off the hook. Even though major hurricanes are rare in the Northeast they have and do occur. Back in 1821 on September 3rd a category four hurricane slammed into the State of New Jersey at Cape May. The Hurricane made four land falls: Virginia, New Jersey, New York, and Southern New England. New Jersey experienced wind just of 200 mph.

In 1869 Hurricane 7 reached 115 mph with a central pressure of 950mb. The hurricane grazed Long Island and made landfall on southwestern Rhode Island.

Then there's the great Long Island Express ( Yankee Clipper) That made landfall on Long Island on September 21, 1938 as a category 3.

The last major hurricane to strike the Northeast was the before mentioned Hurricane Carol . Also during 1954 Hurricane Edna was just below major hurricane strength when she slammed into Massachusetts, just 11 days behind Carol.

The point I'm making is hurricane season in the Atlantic Basin is far from over. And anything can happen. And calls for the seasons demise are premature. All it takes is one hurricane to make landfall near you to completely change your life. So don’t drop your guard. We've seen deadly seasons that started late. Could this be another one, only time will tell.

Rebecca.