We’re moving

closer to the start of the official 2021 Atlantic Hurricane Season. I’ve been

fielding questions as to what I think will occur.

This is long

but it does dive into my current thoughts on how things are looking at this

time.

As is always

the case with my long-range outlooks; if you don’t want to read the analysis

(but you will miss a learning opportunity) you can skip to the verdict at the end.

I will

start with a few basic definitions:

For starters,

a tropical cyclone is the generic name given to low-pressure systems that form

over warm tropical or subtropical seas. When the NHC and I or other forecasters

discuss categories of tropical cyclones we use the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane

Wind Scale. On this scale (which IMO is outdated, but that’s a discussion for

another time) tropical cyclones are rated as follows.

Tropical

Depression: a tropical cyclone with maximum sustained wind speeds less than 39

miles per hour. Also, in order to be classified as a tropical

depression, a tropical disturbance must develop a closed surface circulation

with organized thunderstorms.

Tropical

Storm: a tropical cyclone with maximum sustained wind speeds of at least 39 mph to 73 mph.

When a tropical storm is identified, it formally receives a name. Tropical

cyclones retain their tropical storm status as long as their maximum sustained

winds remain between 39 mph to 73 mph.

Hurricane: a

tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of at least 74 miles per hour.

Category 1 hurricanes have sustained winds of 74 to 95 mph; a category 2 has

sustained winds of 96 to 110 mph Once a hurricane’s sustained wind speed

reaches 111 mph it becomes classified as a major hurricane. Category 3 is 111

to 129 mph, Category is 4 130 to 156 mph, and a Category 5 has sustained winds

of 157 mph or greater.

The Atlantic Basin consists of the entire North

Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, and the Gulf of Mexico. An average Atlantic

Basin season has 12 named storms, six hurricanes, and three major hurricanes.

Tropical

Weather Outlooks:

The official

Atlantic hurricane season has been from June 1st to November 30th.

The National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has been discussing the idea of

changing the official start date of the Atlantic hurricane season from June 1

to May 15th. For the 2021

season the National Hurricane Center (NHC) has said, they have decided to keep

the start date at June 1st. So far, there has been no final decision

on if the 2022 season will be pushed forward 2 weeks to May 15th. But there is still a change occurring this

season. The NHC has said they will start issuing their normal Tropical Weather

Outlooks on May 15th at 8 am. These outlooks usually don’t happen until June

1st.

Analog

years:

These are

the analog years that I’ve chosen; as they seem to match the closest to the

current weather pattern.

1899, 1950,

1956, 1996, 1999, 2003,2004, 2005, 2008, 2012, 2017, 2020

The ones

that I’m placing special emphasis on are 1996, 2003, 2004,2005, 2008, 2012,

2017, and 2020.

Sea

Surface Temperatures (SST):

Hurricanes

thrive on warm sea surface temperatures.

Image from WeatherBell

Image from weatherBell

When we

compare the SST from this time last year, to the what they look like right now.

We can see they look similar. But the eastern Atlantic Main Development Region

(MDR) is a bit cooler, and the north Atlantic in general is a bit warmer.

One of the

major determining factors this season, will be how much the Atlantic south of

25 North warms during April, May and June. For the last four seasons the MDR

was below average in SSTs at this time; but it reversed during the Hurricane

Season, resulting in active tropical seasons. I do expect 2021 will see the

same general idea with the MDR warming to above average SST levels during July,

August, and September.

As was the

case last season; the 2021 hurricane season looks to see an active West African

Monsoon, so as was the case last year, we should see some strong tropical waves

move off of Africa.

A little

more on the West African monsoon season and its impact on the Atlantic

hurricane season.

Saharan Dust

can come off the African coast and move west across the tropical Atlantic.

Saharan dust is the result of lower humidity profiles which adversely impacts

atmospheric moisture and the ability for tropical disturbances to develop and

maintain convective (thunderstorm) activity for further development. So, years

that see a weak West African monsoon season, tend to see weaker than average

tropical waves and disturbances. Over the last 5-6 years, spring rainfall

totals across west Africa has been well above normal. These wet spring

conditions can decrease dust transport off the African Coast during summer.

This in turn elevates the potential for tropical formation in the Atlantic

tropics.

Teleconnections:

The El

Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

The Pacific

Ocean has a significant influence on the Atlantic hurricane season.

Oceanic Nino Index (ONI) is the most common indices used to determine the sate of the ENSO, defined as the three-month average of SSTA in the Nino 3.4 region.

Sea Surface

Temperature Anomaly (SSTA) are generally -0.5°C in Nino 4, -0.3°C in Nino 3.4,

0.1 °C in Nino 3, and 0.9 in Nino 1 + 2 across the Eastern into Central

equatorial Pacific. This would indicate we’re still in a technically in a La

Nina. But there is warming occurring in region Nino 1 + 2. This would seem to

indicate that the La Nina from the Winter, is weakening.

The Climate

Protection Center (CPC) defines ENSO phase anomalies as

El Nino:

characterized by a positive ONI greater than or equal to +0.5ºC.

La Nina:

characterized by a negative ONI less than or equal to -0.5ºC.

By

historical standards, to be classified as a full-fledged El Nino or La Nina

episode, these thresholds must be exceeded for a period of at least 5

consecutive overlapping 3-month seasons.

The new

official CPC/IRI outlook issued earlier this month is similar to these model

forecasts, calling for a 60% chance of La Niña to transition to ENSO neutral in

the Apr-may-Jun timespan. The CPC has a La Nina advisory in effect.

Since late

January, a large area of positive anomalies in the western Pacific has shifted

eastward to around 145˚W at depth. Also, positive subsurface temperature

anomalies from around 25m to the surface have persisted in the far eastern

Pacific Ocean.

Many of the

models are agreeing saying the current La Nina is

going to fade and the summer will feature ENSO neutral conditions. I’m not so

sure of that. I’ve been talking about

the possibility for the current La Nina to try and reestablish itself as we get

closer to the fall. In 2020 we saw what a la Nina hurricane season is capable

of. But many of the analog years I’m

using showed a tendency for a La Nina with some staying power, with some

extending into a 2nd year La Nina.

Atlantic

Multi-Decadal Oscillation (AMO)

The AMO is

an ongoing series of long-duration changes in the sea surface temperature of

the North Atlantic Ocean, with cool and warm phases that may last for 20-50

years.

IMO the AMO

is also a very important teleconnection in long range tropical forecasting. There is some correlation between phases of

the AMO and the frequency of severe hurricane events. This is because it causes

variations in large-scale features over the tropical Atlantic, such as sea

surface temperatures, vertical wind shear, and low-level convergence. the AMO

cycle involves changes in the south-to-north circulation and overturning of

water and heat in the Atlantic Ocean.

In the

negative (cold) phase of the AMO, sea surface temperatures are typically below

normal in the Atlantic MDR, the eastern subtropical Atlantic, and the far North

Atlantic. They are typically near or above normal in the western subtropical

Atlantic.

In the

positive (warm) phase of the AMO, sea surface temperatures are typically above

normal in the Atlantic Main Development Region (MDR), the eastern subtropical

Atlantic, and the far North Atlantic. Sea surface temperatures are typically

below normal or near normal in the western subtropical Atlantic near the United

States East Coast.

The AMO

cycle involves changes in the circulation patterns and overturning of water and

heat in the Atlantic Ocean. This is the same circulation that we think weakens

during ice ages, but in the case of the AMO the changes in circulation are much

more subtle than those of the ice ages. The warm Gulf Stream current off the

east coast of the United States is part of the Atlantic overturning

circulation. The Atlantic Ocean Thermohaline Circulation (THC) is also

something that is impacted by the phase of the AMO. When the overturning circulation decreases,

the North Atlantic temperatures become cooler.

The current

state of the AMO isn’t clear cut, many experts disagree on whether we are in a

positive or negative AMO phase. IMO we’re still in a positive (warm) AMO phase.

During a positive warm phase there isn’t

a real correlation between the AMO and the frequency of tropical storms and category

1 and category 2 hurricanes – But during warm phases of the AMO, the numbers of

tropical storms that mature into severe hurricanes is much greater than during

cool phases, at least twice as many.

Since 1950

the seasons with the most ACE are 2005,1995, 2004, 1950, and 1961 have all

occurred during a positive AMO phase. Also, the five Atlantic hurricane seasons

since 1950 with the least ACE were 1983, 1977, 1972, 1982, and 1994 have all

occurred during a negative AMO phase.

Pacific

Decadal Oscillation (PDO)

The Pacific

Decadal Oscillation (PDO) is a long-lived ENSO-like pattern of Pacific climate

variability. While the two climate oscillations have similar spatial climate fingerprints,

The PDO and ENSO influence sea surface temperatures, sea level pressure, and

surface winds in very similar ways.

While ENSO

is primarily an interannual phenomenon, the PDO is decadal in scale. The PDO

phases can be associated with El Nino or La Nina. The positive phase of the PDO

which has the water surface with warm temperatures in the equatorial Pacific,

can enhance an El Nino episode, amplifying the effects of the latter. This same

phase of the PDO would weaken the La Nina events that would occur during this

period. Similarly, during a negative phase of the PDO, events La Nina would be

rather enhanced, and El Nino events would be weakened.

Currently

we’re in a Negative PDO.

The negative

PDO and La Nina favor increased Atlantic hurricane activity.

The

Quasi-Biennial Oscillation (QBO)

During QBO

negative (easterly) years, tropical cyclones tend to form north of the main

development zone. Tropical Cyclones also

seem to form closer into the CONUS, increasing the likelihood of a landfall. So,

this could counter that idea of the La Nina allowing storms to form father east.

The Madden-Julian

Oscillation (MJO)

The

Madden-Julian Oscillation is a major fluctuation in tropical circulation and

rainfall that moves eastward along the equator, and circles the entire globe. It takes on average 30 to 60 days to complete

that trip around the globe. The pattern typically starts in the Indian Ocean,

it then moves east into the Pacific, and then into the Atlantic.

The MJO has

two phases, one is the enhanced precipitation phase; the other is the

suppressed precipitation phase. that

bisect the planet. Usually, half of the planet will be experiencing increasing trend in rainfall amounts, while

the other half of the planet will experience drier conditions.

Normally,

when the enhanced phase of the MJO pushes into the Gulf of Mexico or the

Atlantic Ocean, tropical activity is more favored due to an increase in rising

air (Convergence) and decreased windshear, which leads to thunderstorm

(Convection) development. So, during this phase, tropical cyclone development

or strengthening is possible. On average Major are up to five times more likely

to develop during the enhanced phase of the MJO, while hurricane formation can

be up to four times as likely.

When the

Atlantic Basin is under the suppressed phase of the MJO. The phase will hinder

tropical development; because of sinking air (divergence) along with increased

windshear. That doesn’t mean there can’t be tropical development, but it makes

it much less likely to see thunderstorm development across the tropical basin.

This will often lead to a multi-week lull in tropical development in the basin.

Phases 1 and

2 are the phases most favorable for Atlantic tropical activity.

The MJO will

end up being a wildcard, as it is unclear as to how it will influence the

Atlantic Hurricane Season.

A little

this and that

There is a

coronation that 2nd year La Nina ends up with tropical cyclones developing

farther east. A negative PDO tends to

lead to stronger tropical cyclones. A

positive Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) tends to lead to increase

tropical activity.

Accumulated

Cyclone Energy (ACE):

Ace is used

to measure the intensity of a hurricane season as well as individual tropical cyclones. The higher the number the

more active the season and the danger level during the season and the greater

the damage potential of individual storms.

Based on

what I see right now, I’m thinking this year’s Atlantic ACE will be between

150- 200.

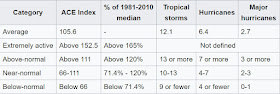

Here is a

chart that shows how ACE values generally corresponds with tropical cyclone

activity.

1933 is the record holder

with an ACE of 258.57 that season saw 20 named storms, 2005 comes in 2nd

with an ACE of 250.13 that season saw 28 named storms (which was the record,

until 2021. In spite of the record setting 2021 season, which saw 30 named

storms; 2021 comes in at 10th place in terms of ACE. 2021 ended up

with ACE of 182.22. Why was it so low

but had a record-breaking number of named storms? Many of the storms last season were weak

short lived tropical cyclones; Also, the tendency of the NHC naming storms that

wouldn’t have been named in previous years. The increased number of named

storms is due in part to increased technological methods.

List of

names for the 2021 Atlantic Hurricane Season:

It’s too

soon to know, if this season will be as active as the record-breaking season of

2020. In 2020 ran out of names on the traditional list of names, and had to go

into the Greek alphabet. Last season they used Alpha, Bata, Gamma, Delta,

Epsilon, Zeta, Eta, and Theta.

Another major change for 2021 is that the World Meteorological Organization has voted to eliminate the use of the Greek alphabet in future seasons because it created potential confusion. Starting in the 2021 season, there will be a supplemental list of names that will be used in the event we run out of hurricane names in a given year.

For 2021 the official list of names will be…

Ana

Bill

Claudette

Danny

Elsa

Fred

Grace

Henri

Ida

Julian

Kate

Larry

Mindy

Nicholas

Odette

Peter

Rose

Sam

Teresa

Victor

Wanda

The supplemental

list of names

Adria

Braylen

Caridad

Deshawn

Emery

Foster

Gemma

Heath

Isla

Jacobus

Kenzie

Lucio

Makayla

Nolan

Orlanda

Pax

Ronin

Sophie

Tayshaun

Viviana

Will

The Verdict:

I am

forecasting an above average tropical season in the Atlantic Basin.

Total named

storms 18-24

Hurricanes

8-15

Major

Hurricanes 4-8

The Landfall

Threat

Any long

track tropical cyclones that form in the eastern Atlantic moving west, the turn

to the north could come farther east than we saw last year. The analog data

does support the idea that a ridge is likely over the Northeast and southeast

Canada.

This would

mean North Carolina and South Carolina, along with the Eastern and Central Gulf

Coast (from the Big Bend of Florida over to Louisiana) would be the area of

greatest concern. The Leeward Islands, the Northeast Caribbean, entire Florida

Peninsula, and the Bahamas will also be at a heightened risk. The pattern that looks to develop, would mean

the Northeast and Atlantic Canada will have to be very watchful this

season. Last year we saw the western Caribbean quite

active. For this season I think the active focus will shift north and east of

there. The central and eastern Gulf is likely to be much more active than the

western Gulf.

Right now,

I’m thinking for the CONUS there is a chance of 5-6 landfalling hurricanes. 1-2

of these could be major hurricanes of Category 3,4, or even 5.

Well, that

is it for part 1. I will most likely issue part 2 around mid-April. Then if a part 3 is needed that will be issued

around the middle of May.

I hope you

found this interesting and informative. Remember this is only part one, so this

could all change as the season gets closer. But as of mid-March, this is what

looks to occur.

Part 2 can be found here