Well, this is it, I’m finely ready to post part three, with

my thoughts for the 2022 -2023 winter.

November started out very warm, due to that strong ridge in

the Jet Stream, that allowed a lot of warm southern air to invade the Northeast

and Middle Atlantic region. with the entire region breaking several record day

time highs and setting record nighttime high lows. But by Mid-November that all came to a

crashing halt. This pattern change was

well telegraphed, and I warned all y’all about it several weeks in

advance. With the pattern flip and return

of the cold, and with Thanksgiving behind us many are now thinking about the

winter and what that might bring.

This will be the third and final part of my 2022-2023 winter outlook series for the Northeast and Northern Middle Atlantic region.

Like the winter before it, the 2021-2022 was a La Nina

winter. Both winters behaved very much like we would expect a La Nina to act

like. During the winter of 2021-2022, the polar vortex was relatively strong,

but it did stretch a few times bringing some cold air into the Northeast. While

the Northeast and Northern Middle Atlantic Region didn’t see a real cold winter,

temperatures outside of a large part of Western Pennsylvania, where overall

temperatures averaged well above average, most of the rest of the region, ended

up with overall temperatures right around average.

Precipitation wise, the Northeast and Northern Middle

Atlantic Region, saw a large variation. Most of the region saw below to well below

average, with far northern New York State and far eastern Maine, ended up

overall average, with far Western New York State and Pennsylvania ended above

average. Snowfall wise much of the region ended up with below average snowfall.

Last winter in the major cities, Washington DC ended up with

13.2 inches, which is about half of an inch below their average. New York City

ended up with 17.9, which is almost 12 inches below the seasonal average,

Boston ended up with 54 inches.

Climate.gov images based on CPC data.

Winter 2022-2023:

Let me address the elephant in the room. There is no doubt that globally, nationally, and locally we’re warmer on average than we were 50 years ago. I’ve never said we’re not warming; I’ve just disagreed with the notion that most of the warming is due to human caused warming. But no matter your view on the subject, we are warming. The extra warming in the atmosphere, means the air can hold more water vapor, so during the summer we have a chance to see more heavy rain events. During the winter, it means we have a better chance to make snow lovers happy. Those warm SST offshore combined with the large temperature gradient (difference) between the Atlantic and land and the extra moisture in the atmosphere, leads to a greater chance for widespread winter precipitation events. But potential doesn’t mean it will happen with every storm that comes through, as aways it’s a matter of timing and track. Because atmospheric temperatures are generally warmer than they were 50 years ago, it can make it more difficult to sort out the pattern, for what may or may not occur.

The pre winter pattern:

The pattern over the last 7 to 8 months has been busy across

the Northeast. We had several strong

inland and coastal lows, some of these ended up stalling off the Coast. Then the

first in a series of Summer and Fall Nor’easters occurred in Mid-August. The

number of coastal storms and early season nor’easters represents a pattern than

can repeat throughout the season. We also had tropical impacts from Nicole and

Ian over parts of the region. October

landfalling East Coast hurricanes and landfalling Florida November Hurricanes,

do have a correlation to colder and a more active winter pattern here in the

Northeast. We had an East Coast Landfall

in November 1935, the following winter of 1935-1936 was extremely cold and

snowy. Then we had Hurricane Kate, make an East Coast landfall in November of 1985. The

winter of 1985-1986 was extremely cold and snowy.

Polar Vortex:

When the Polar Vortex weakens and or wobbles, cold arctic

air moves into the lower latitudes. This

cold air can drop into Asia, Europe, or North America.

Our winter pattern started with Hurricane Fiona in

September. When Fiona made landfall on Atlantic Canada with 105 mph winds, it

started the line of dominoes to fall, as Fiona continued into the Arctic

Circle.

Nicole led to a weakness in the atmosphere that resulted in

colder air sweeping into parts of the region, as well as yet another

nor’easter.

Hurricane Martin was the furthest North forming November Hurricane in the Atlantic on record.

All of this tropical activity had a impact on the upcoming winter pattern.

We just had our record-breaking Lake Effect Snow Event, due

to the Polar Vortex buckling sending very cold air over the warm Great Lakes.

While this wasn’t a major snowstorm across the region, it was the result of an

arctic blast. Currently the polar vortex is redeveloping. The winter of

2014-2015 saw a similar severe lake effect event that occurred on the 17-19th

of November. In fact, many winters that

saw early lake effect events like this ended up being active with below average

temperatures.

But correlation is not causation.

Sea Surface Temperature Anomaly:

Looking at the latest global ocean anomalies, you can see

the cold La Nina standing out in the tropical Pacific. We also see cooling

developing along the west coast of North America, with a very warm pool in the

northern west Pacific

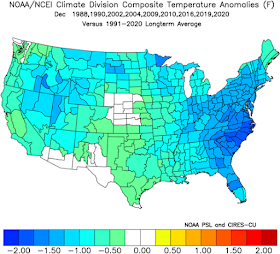

Analogues:

For the analogues I’ve finely come up with these six years.

1935-1936, 1966-1967, 1984-1985, 1995-1996, 2010-2011, 2013-2014. The winter of 2014-2015 pattern didn't match the pattern, quite as well, but it could have been used, If I had used seven analogues, it would have skewed the results to even a colder and snowier winter.

.

Teleconnections:

This winter is featuring a rare tropical dip La Nina. The La

Nina should be moderate to weak. Currently the La Nina is still basically east

based. The current strength of the La Nina is moderate, we can see this with

the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) value over the last 90 days has been 14.47,

when the SOI is generally between 14 and 20, the La Nina is considered

moderate.

Here is a look at the IRI probability forecast. It predicts

the current moderate La Nina will weaken and become weak during the 2nd

half of winter, likely transitioning to neutral during spring 2023.

I discussed the La

Nina in parts one and two. So, no need to go into a lot of detail.

Pacific decadal Oscillation (PDO):

Looking at the Sea Surface Temperature Anomaly above, currently

the PDO is generally negative. But, in part two, I talked about how the PDO

looked to be trying to turn positive. The cooler SST pool in the Gulf of Alaska

has expanded, and as I said above there does appear to be cooling trying to

develop off the West Coast. So, it is still possible the PDO could become

neutral or go positive. The warm Atlantic stands out as well.

The Quasi-Biennial Oscillation:

QBO is looking to be positive (westerly)

The QBO deals with winds in the stratosphere above the

equator. This belt of winds circles around the equator. The wind direction

generally switches direction every 14 months.

On average winters that feature a positive QBO, tend to be

milder for the Eastern CONUS. This is because there is less tendency for the

polar vortex to become disrupted.

Pacific North American Pattern (PNA):

We have the higher heights in the Gulf of Alaska, lower

heights in the Aleutians, and higher heights over Florida. So, we should see the PNA become predominantly

positive this winter.

Eastern Pacific Oscillation (EPO):

The EPO is negative, with the current strength of the

ridging into Alaska, I think the EPO should remain mainly negative for much of

winter 2022-2023. This will help in displacing the cold air into the Great

Lakes and East.

Indian Ocean Dipole

(IOD)

The IOD deals with variations in the difference between the

SST in the tropical Western and Eastern Indian Ocean.

The IOD was negative, but it has been weakening. The most

recent value is -0.06 which means it is now- neutral. When the IOD is negative, Lower 48 typically

see warmer than average temperatures. With the IOD currently neutral and

heading toward positive. It would be an indicator for cooler than average

temperatures.

Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation:

The AMO is a very long term (decadal) oscillation, meaning

it doesn’t flip every few years. Currently, the AMO is in its positive (warm)

phase AMO. Looking at the chart (blue is negative and red is positive), we can

see the last negative phase went generally from the early 1960’s into the early

2000’s. Then we flipped to the positive phase, outside of a few variations

we’ve been long term phase ever since.

Why is this important? Warm SSTs in the northern Atlantic,

can increase precipitation amounts for us here in the Northeast and Middle

Atlantic Region.

Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO):

The MJO is a tropical pattern, involving an eastward

atmospheric pattern and rainfall, that circles the earth every 30 to 60 days.

It broken down into 8 phases. It is known

to have big influence a variety of weather patterns around the globe. There is

a significant relationship between the phases of the MJO and the frequency of

nor’easters.

When the MJO is in phases 7, 8, and 1, chances of snowfall

are increased. Chances of snowfall are decreased for MJO phases 4 and 5. Research

has shown Nor’easters are more numerus when the MJO is in phases 7 and 8.

Teleconnections are important, but they’re not the end all

say all. They will give you an overall broad brush as to what the pattern looks

to generally do. But they don’t tell you where the ridges and troughs will

setup, or where the individual storms will track.

Eurasian and Northern Hemisphere Snowfall Extent:

Snow extent has grown very fast over the last 30 days. Snow

extent over East Asia has been fairly robust and currently is above the 30-year

average. In fact, snow extent across the entire northern Hemisphere is well above

average. Russia is almost completely

covered in snow, Alaska and Canada have been inundated with snow, and extends

farther south over the Lower 48 than the average. But the snow extent is the

largest it has been in 56 years.

Extensive snow extent early in the season is an indicator of

the amount of colder air available in the pattern has we head into Winter. But

across Western Asia, snowfall hasn’t been as pronounced. The idea that snow extent is deep and

expanding across Siberia, is a good sign for an expansive pool of cold air over

that region. If this happens, there is a much greater chance for disruptions in

the Polar Vortex, leading to chances for cold outbreaks across North America.

When we look back at the winters that had a similar snow

extent; the Northeast and Middle Atlantic had overall cold and snowy winters.

These winters also featured severe lake effect snow storms; we’ve just had one 10 days ago. With another big lake effect event occurring tomorrow.

Clippers, Cutters, Miller B nor’easter and Miller A nor’easter

Clippers, drop out of Western Canada drop into the Upper

Midwest and then move somewhere between the Northeast and the Delmarva

Peninsula. These typically bring light to moderate snow events.

Cutters, move up the coast along the Appalachian Mountains. Depending on how they track they can bring a mix of precipitation types.

Miller B’s many times start out as a clipper type system,

but they end up transferring to a 2nd low offshore. These complex

storms move fairly slow but can bring big snow but who sees heavy snow depends

more on timing.

Miller A’s typically start over the Gulf of Mexico then

moves up the Coast. Miller A’s are what is normally called a classic Nor’easter,

and can move slowly or very fast. Miller A’s can bring widespread heavy snow

who sees how much depends on the storm track.

November has been very active, we’re seeing lots of storms

moving up into the Great Lakes (which is quite common this time of year), and

more than a few coming up the coast. These storms have brought a lot of winter

type with them, when we look back at winters that had similar November’s they

ended up being quite wintery.

The last part of November has seen a warming trend. Looking

at the teleconnections this mild pattern should last into around December 5th.

After that, a much more wintery pattern develops. At that time, we will have a

strong ridge across Alaska and Greenland, as a result of the negative EPO,

negative AO and the negative NAO. We

should have troughing setting up over the Plains for the end of November, this

would likely expand east as we get into December. This is likely to be widespread

and long-lasting cold East of the Rockies, with chances for snow storms due to

that active subtropical Jet. The MJO is

looking to move into Phase 7 as we get into December, As I said above, when the

MJO is in phases 7,8 and 1 the chances for coastal snowstorms increases along

the East Coast. We also look to have another disruption in the Polar Vortex, for the first part of January.

Many outlets are keying on La Nina being the major influence

for this upcoming winter season. Typically, during La Nina the subtropical jet

stream is weaker, which means less moisture available over the East Coast, with

a lesser chance for phasing developing for bigger snowstorm potential. But less

moisture doesn’t mean no snow…when we average all La Nina years, snowfall

patterns across northern New York State and northern New England tend to be

above average, with the rest of the region typically seeing below average

snowfall. Since no two La Nina’s are exactly the same, that can vary.

For this winter, I’m betting on La Nina not being typical or

the main driver of this winter. Many times, during La Nina we see a predominate

zonal flow, with a firehose of moisture coming off the Pacific and working

across the CONUS. For winter 2022-2023 I don’t see that being the case. There is a lot of amplitude over the Pacific,

with a steep ridge building into the Aleutian Islands. We have a very active

southern subtropical jet stream. I covered the reasons for this in parts one

and two. This active subtropical jet stream is more than likely going to

distort the influence from La Nina. As I said in part one and two. The Hunga

Tonga Volcano huge water vapor ejection is the reason for the subtropical jet

being and staying so active, due to the imbalance it set into motion. So, it

will have a big impact on our winter weather.

What could go wrong:

Southeast ridge when this pushes north it might overwhelm

the pattern, especially for the Mid Atlantic. The Tonga Volcanic eruption is

another wild card. An event like this that pushed so much water vapor into the

atmosphere, has never been witness in recorded weather history, so we’re in new

territory. If it behaves different than I anticipate it will throw the entire

outlook into the dumpster. Another wild card will be the chance that this La Nina will be more of a hybrid than I anticipate . The MJO will

be another wildcard. MJO phases will be critical in how the winter storms

behave.

OK so what about the Northeast and northern Middle

Atlantic this winter:

To call for the type of winter I am, is a bold statement, most outlets are calling for the exact opposite. But I have to trust in the data, and what I see!

I still think this is going to be a front-loaded winter. Winter

starts early with December being overall quite cold. With the Pattern setting

up, there should be several snow chances. It does look like we’re going to see another polar

vortex event during the first 10 days of December. We could see it very cold near or over Christmas, with the chance for some snow. As I said, in the earlier

parts of this outlook, the polar vortex for this winter is looking to be fairly

weak. This winter is going to be very

active, so the idea of a weak polar vortex is a good thing if you want to see

cold and snow.

So, with December into at least Mid-January looking to be

generally cold and snowy. That’s next? Well, I think we’re going to see a lull

develop for the last part of January and well into February. But that doesn’t

mean there won’t be cold shots, depending on timing there could be chances for

snow during this time as well. Then for

the end of February into March we could see a better chance for a few larger

snowstorms.

The pattern I’ve described, means this isn’t going to be the

type of winter we’ve become accustomed to the last several years. The pattern

means several nor’easters are likely this winter, but not all of them will have

a track that brings widespread heavy snow.

Well that's it....We will see how things work out.

.png)