Here is the

links for part one and part two.

Part two

The Days

have been getting shorter and the temperatures have been getting colder. This

time of year, many of y’all, want me to look into my crystal-ball, and try to

give you a leg up on what might happen this winter.

Please keep

in mind, longer-range seasonal predictions often involve the broader picture of

what’s to come. Outlooks like this cover the overall region. And don’t go into

local detail, for individual in your back yard snowfall amounts. As we see

every winter snowfall extent and amounts can vary greatly, over relatively

short distances.

This outlook

will be more in plain speak. Details on what teleconnections are and what they

mean, can be found in part two.

The signals

I use to try and figure out how things will be this winter are very mixed. So

that is telling me this winter is going to see a lot of variability.

If you don’t

want to read through the entire outlook, you can skip to the bottom to the conclusion.

But you will miss the reasons I decided on the end result.

The

analog seasons:

Over the

course of this three-part outlook, I’ve been talking about analogs. Here is the

list of analog seasons that I’ve settled on.

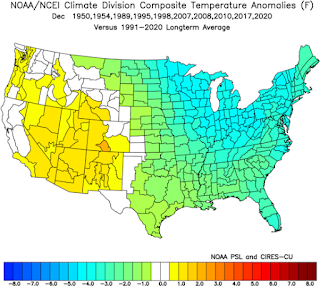

1950 -1952,

1954-1955, 1989-1990, 1995-1996, 2007-2008, 2008-2009, 2010-2011, 2011-2012,

2017-2018, 2020-2021.

2010-2011 is triple weighted, and 2017-2018 is double weighted.

Teleconnections:

Image from Tropical Tidbits.

La Nina…

During La Nina,

we typically see the jet stream come out of Western Canada, dip across the

Upper Midwest that then move somewhere over the Ohio Valley and then into the

Northeast. On average temperatures are

warmer near the jet stream and south of it.

The Northeast pattern tends to be active.

This is a double dip La Nina, meaning this is

the 2nd year in a row for La Nina. 2nd

year La Ninas tend to be weaker than 1st year ones.

Some weather

outlets are calling for an east based La Nina this winter, others are calling

for a general Pacific Basin wide La Nina. The type of La Nina is important, as

these variations can make for much different winter outcomes. Everything I’ve

been looking at, has me thinking this is going to end up being a La Nina Modoki

(hybrid La Nina) When we look at the subsurface temperature anomalies,

subsurface temperatures are very cool, and look to be more west based. La Nina

Modoki events are very rare, even rarer than El Nino Modoki. We had a La Nina

Modoki in 1989. The winter of 2010-2011 was another La Nina Modoki.

If this does

become a La Nina Modoki, it would tend to have the storm track a little farther

north than when we see an east based La Nina. This would setup the Northern Mid Atlantic

region as the battle zone. This would mean the Northern Mid Atlantic and those

close to it, would see a roller coaster of temperatures fluctuations that could

vary from week to week. This could have large implications was to precipitation

types during the winter.

We also see

a lot of variability when it comes to La Nina, especially 2nd year La Ninas. 2011-2012 was a second year La Nina, that

winter was dismal with warm temperatures and well below average snowfall. But 2000-2001 was a second year La Nina that

was the opposite. So, while La Nina can

be a big driver, we have to look beyond the ENSO.

Southern

Oscillation Index…

I’ve been

talking about the pattern change for quite some time. One of the teleconnections

I watch, is the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI). When we see big changes in

the SOI it can affect the North American pattern two to three weeks down the

road. Looking at the chart we can see the SOI take a nose dive a little before

Halloween. This is strongly connected to the very cold pattern setting up for

this weekend into the rest of November.

Strong La

Nina have SOI 30-day values up around

the upper 20’s into the 30’s. The last moderate La Nina had the mid-teens to

mid-20’s. So far this La Nina is barely making it into the 11’s. So right now,

this is quite weak. There isn’t really

any drive here that is trying to push the SOI into a strong positive state.

So I’m thinking this La Nina is going to be weak, instead of moderate or strong.

Eastern Pacific

Oscillation and Western Pacific Oscillation…

Right now,

the EPO is positive and the WPO is negative. The ensembles are in disagreement

as to where the EPO is heading, But I think the EURO has the better handle on

things. The reason for backing the EURO has the do with the WPO. The WPO is

strongly negative. The ensembles are in rough agreement that the WPO will stay

primarily negative as we move into the first half of Winter. The

WPO typically rules the roost with it comes to EPO. A negative WPO tends to

force the EPO back to negative during those times the EPO becomes positive.

Images from WeatherBell.

The North

Pacific Oscillation…

The PDO is important because La Nina is located in the

Pacific and will be a driving force.

This PDO is Negative and on average that tends to drive colder air to

the Eastern US.

Quasi-Biennial

Oscillation…

Right now,

the QBO is negative. Typically, when the QBO as negative in November, along

with winters that experienced a weak La Nina. The QBO stayed negative for December

into March. When this is Negative during

a Moderate La Nina, we tend to get more snow.

The Pacific North

American Pattern…

The PNA is

currently slightly negative, if we want abundant cold air this isn’t a good thing.

When the PNA

is negative we tend to see a zonal (west to east) flow over the northern CONUS. The positive phase leads to a meridional (north to south) flow.

The Positive

Phase brings warmer/drier weather to the West and colder/wetter weather to the

East.

The PNA also

reflects the strength of the Aleutian Low.

Cold Pool

in the Gulf of Alaska:

Typically, during

a La Nina, we tend to see an area of 500mb low pressure stubbornly stay over

the Gulf of Alaska. This kind of setup

makes it hard to get much in the way of cold infiltrating into the eastern half

of the CONUS, as we end up with a negative PNA. We will have to watch to see if

it can be replaced with ridging during the winter or at least shift enough

Southwest of the Aleutian Islands to allow more of a positive PNA. The placement

of the cold Pool is indicating that we might see the low pressure break down or

move more to the southwest. This would lead to a better chance for cold air

into the East do to a positive PNA.

For true

cold air in the wintertime into the central and eastern CONUS; we need a

snowpack over a large part of Canada. This would help break down the Low in the

Gulf of Alaska. Otherwise, it is very

hard to have polar and arctic airmasses drop into the CONUS. This goes back to the zonal flow I was

talking about earlier, where you get milder Maritime Pacific and Continental airmasses.

The cold

pool reaches the Aleutians and south of there. This means we should see a

western ridge develop, as the western trough moves west. This would increase

the odds of a trough developing into the Midwest and Northeast, leading to cold

air trying to overwhelm the pattern for December into the early part of January.

Eurasian Snow

Cover / Arctic Sea Ice Extent:

Two other

teleconnections that I use are Eurasian snow cover, and arctic sea Ice extent

during the month of October. The use of these two has fallen out of favor in

most outlooks. But I still use them as there is a weak correlation

between them and overall winter weather here in the Northeast.

Eurasian Snow

Cover…

From the

graph of the Eurasian snow cover trends leading into

the Northern Hemisphere winter from 1967 to 2021. This chart is showing the

snowfall extent during the entire month of October 2021. From the graph above,

you see, overall, we’re running on the lower side of average. The winter of

2017-2018 had slightly less snow extent. Generally, the lower the Eurasian October

snow extent, the milder the East Coast winter.

On average

the more area snowfall coverage in Siberia in October, leads to better chances

for colder winters on the East Coast.

Sea Ice is

another thing I look at in October

Sea Ice Cover…

Average

monthly air temperatures were well below freezing across much of the Arctic

Ocean in October. As a result, the sea ice extent has been quickly growing, and

by the end of October, ice covered most of the Arctic Ocean. Overall, the ice

extent remained below average for this time of year in the Barents and Kara Seas,

as well as within northern Baffin Bay and the East Greenland Sea.

In October, the sea ice extent ended up higher than any year since

2015, as well as higher than observed in 2007, 2011, and 2012.

As has been

the case for many recent years, sea ice has been running below normal, in many

cases due to long-term warming global temperatures. Although still under a

degree of research, there is a correlation that shows generally the less sea

ice present in the area of the Barents-Kara Sea, east of Greenland, moving into

the winter season, the greater the likelihood of cold snaps over North America

as the polar vortex swoops in every now and again.

Stratospheric

Warming:

I’ve been talking about the Sudden

Stratospheric Warming (SSW), that just occurred and the one that looks to take

place sometime in December. If we indeed see a December SSW it would correlate

with the cold December idea I’ve been floating around for the last few months.

Climatology:

The

Hurricane Season…

There is

some correlation between Hurricane activity in the Atlantic Basin and the

following winter.

looks like

2011 was the best analog. Especially with how the season shut down.

2004 and

2007 are also both good examples of seasons that significantly slowed down

after September. In 2004 the early season was quiet, but the months of August

and September combined produced 12 Named Storms, 9 Hurricanes, 6 Major Hurricanes.

After that there were only 3 marginal, short-lived storms.

2007 was

similar to 2021 in that there were lots of weaker tropical storms. September

had 8, but almost the whole month of October elapsed before Hurricane Noel

developed at the end of the month.

This year we

had Hurricane Sam, which racked up a lot of ACE points, we also had Tropical

Storms Victor and Wanda, these helped to redistribute heat from the tropics

into the North Atlantic. I feel this

will help make it more likely for a negative NAO, leading to a better chance

for North Atlantic Blocking to support cold air for at least the first part of

winter.

The Warm

Fall…

October has

been very warm overall. The last couple

of days have been cool. But the month as a whole, is one of the warmest

Octobers in the Northeast over the historic record.

When we look

at past years that had similar patterns to this one, we come up with a front-loaded

winter, like I’ve been talking about over the last few months.

Winters

after a wet October tend to see above average snowfall across New York State

and New England. Throw in the Warm

Summers and we even greater chances for average to above average snow.

This has

been a wet fall, on average very wet Octobers tend to be during La Nina’s. This

coronation is likely because the pattern is telling us we’re going to see a lot

of activity.

On average

Warm Summers and Falls when added to La Nina.

Some of

these occurred in:

1955-1956

2005-2006

2016-2017

Cold Mays…

There is a

moderate relationship between cold Mays and years that had an active hurricane

season, lead to an early start to winter in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic.

Years that

had cold Mays, Warm Octobers, and Octobers that had an SSW event. 1950,1954, 1955, 1960, 1979, 1989,1995.

Those winters had cold Novembers and Decembers.

Lake Effect…

Every year

the lake belts deal with lake effect.

We’ve been

very warm overall, so Erie and Ontario are very warm. Right now, the Lower Lakes are about 4-5

degrees warmer than what is considered average for November. Right now, Lake Erie has water temperatures

of almost 59 degrees, the warmest on record, more than 4 degrees above average.

Lake Ontario water temperature is at almost 57 degrees, the warmest on record,

more than 5 degrees above average.

Does that

mean, everyone near Lakes Ontario and Erie will see huge snowfall events? In

answer, that depends.

Which

leading us to The Big Question: Will these warm water temperatures play a role

in increasing lake effect snow in early winter?

First, the

actual water temperature isn't the prime factor when it comes to lake effect

snow. It’s the difference between the

lake water temperature and the air temperature of the colder air moving over

the lake surface.

Typically, as

we approach winter, the water temperature begins to drop at roughly the same

rate in September and October regardless of the highest water temperature

reached during the summer. This year the fall was very warm, so the lakes

stayed a little warmer later into the year. But by the time we get into December, the

water temperatures will likely cool off back to around average.

So, while

the lake is primed, lake snow is all about potential. Things have to line up. We need the timing

of the cold air incursions and the storm tracks to a line; Also, the Wind

direction has to be right, so areas that depend on lake snow can see large

variability within the typical snowbelt areas.

The pattern

does support several shots of cold air over the next few weeks. So, those

downwind of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario are at risk for heavier lake effect snow

events during the early season.

Solar:

When dealing

with the long term, the sun is the main driver of weather and climate on the

planet. We’re just coming out of a solar

minimum. During the winter, solar activity should stay at relatively low

levels. Low solar seems to favor a persistence

for more in the way of high latitude blocking. With higher-than-average

geopotential heights around Greenland and Iceland. The Great Lakes and East Coast tend to see

more in the way of cold air intrusions during low solar winters, which

increased the odds of seeing more snow.

Storm

Tracks:

The storm

track pattern for this winter…

Typically,

during La Nina winters we see many storms cut to our west and move over the

Great Lakes. Most of us know a storm cutting to our west places the Northeast

and Mid-Atlantic in the warm sector.

The

developing pattern supports the idea for at least a few Miller-B events. A

Miller-B means a storm that approaches the Northeast, and then transfers its

energy to the coast. These types of

storms tend to impact eastern New York State and New England more than they do

the Middle Atlantic and the rest of the region.

In October

we had to early season nor’easters. Giving the setup that looks to set up would

tend to favor a more easterly track for coastal storms. But if we can get

blocking which lines up with a coastal storm track. If this happens the Mid

Atlantic into southern New England could end up with at least one big snow

event. If my idea of a La Nina Modoki setting up, would make the chance for a

few coastal storms having at least some impacts.

Behind these

storms we typically see cold air outbreaks, where Clippers can provide light to

moderate snow events.

Conclusion:

December…

The reasons

I’ve shown above, support the idea of an early start to winter, that I’ve been

pushing for a while now. We’re into Mid

November and the pattern has already flipped to one that is overall cold for

this time of year. December looks to be very cold overall. December looks to be

very snowy as well.

January…

The CPC is

expecting the La Nina to peak mid-winter. But there are signs that the La Nina

may peak before then. So, I believe

January will end up overall mild. The pattern will still be very active, with

most of the storms cutting up through the Great Lakes. There could be a few

Miller-B storms that end up forming, but these would likely miss the Mid Atlantic,

but could favor New England with a snowstorm or two.

February

into March…

February is

the month; I’m having the biggest trouble with.

I believe it will start out with above average temperatures. But as we

get past mid-February, we could see some colder air try to move into the

Northeast and Middle Atlantic. But overall February will be a warm month. On average the month of February, has the

region seeing their best opportunity for storminess. But with the southeast ridge pushing north,

it would come down to timing of events as to which kind of P-type we end up

with. March will likely see a

continuation of the general February pattern. As the La Nina should be starting

to fade, we would be relining on other teleconnections to play a role, but the

area will likely see March with overall slightly below average, which would be similar

to the last several winters. So we could see some storminess that leads to

increased snow chances for the end of February into March.

So, this

winter is going to be somewhat similar to last winter, but with a bit more bite

to it when and where it does get cold and snowy, it also looks erratic with

changeable jet stream patterns over the December through March period, more so

than last winter.

My overall

idea for snow amount and temperature across the region…

For the

Northern Mid-Atlantic region, the pattern supports the idea of an overall above

average winter when it comes to temperature. This winter will see a very active pattern. As I said

earlier this area will be where the battle ground sets up between the colder

air to the north and the warmer air to the south. While the general storm track

won’t be favorable for a giant snowstorm, it does feature a good chance for

small to medium storms. So, while I think the overall precipitation amount will

be above average; the warmer overall temperatures will increase the odds for

more rain and ice events as opposed to snow events, so overall seasonal

snowfall will likely end up 75%-90% of average.

For Pennsylvania

into western New York State and the Southern Tier along with Southern New

England… This part of the region will likely see overall temperatures slightly

above average. But with overall temperatures closer to average, this area will

likely see conditions similar to last winter. With an active storm track, snowfall

will likely end up slightly below average to slightly above average. so overall

seasonal snowfall will likely end up 90%-110% of average.

For the rest

of New York State and New England. This part of the Northeast will likely end

up with overall temperatures slightly below the 30-year average. With the

pattern that looks to setup I’m thinking overall snowfall will end up being

100% to 130% of the average.

As far as

lake effect, the traditional snowbelts should end up with an average to above average

year. Inside the lake snowbelts, snowfall can very greatly over very small distances.

Some outlets

change these seasonal forecasts has conditions change during the season. But I

don’t like to do that. I release an outlook, and I live with it. I don’t know

how it will work out until the end of the season.

Well, that’s

it, I put a lot of thought in this and tried to find a balance between the

conflicting signals. Remember this is showing the overall snow and temperature for

the entire winter. There can also be variability inside the general three areas

found on my maps.