Here is part

two of the 2024 Atlantic hurricane outlook. This is an extension of my analysis from my 2024 Hurricane

Outlook Part One. I will take you through the reasons I think this is going to

be a very busy season.

The 2024 hurricane season is getting closer. The Hurricane Season starts on June 1’s and will end on November 30th. The 2024 Hurricane season should be quite different as we transition from El Nino into A la-Nina.

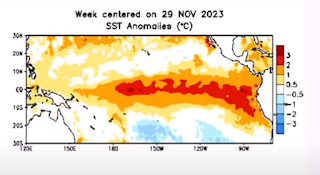

We still

have slightly above average SST in the equatorial Pacific. But these are much

cooler than they were a few months ago. We also have very warm SST in the

Northwestern Pacific.

Both of

these will play a big role in this year’s hurricane season.

In the

Atlantic SST anomalies across the Main Development Region (MDR) (the area

between the Lesser Antilles and the West Coast of Africa) are well above

average. The SST in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico (GOM) aren’t quite as

warm, but they are still above average. As we approach the heart of the

hurricane season, these Atlantic Basin SST will become even warmer.

Average

water temperatures since January in the Atlantic’s Main Development Region are

2 °F above last year, crushing previous highs by

almost 0.6 °F.

Another

thing we see in the Atlantic is cooler SST in the North Atlantic north of the

MDR. This is another indicator of an active season. As this temperature

contrast helps supply lift that the tropical waves can use to make it easier

for convection to develop in the MDR that could lead to Tropical Cyclone

development.

The ENSO is

a climate pattern that involves changing water temperatures in the Central and

Eastern equatorial Pacific. There are three statuses of the ENSO: La Nina,

neutral and El Nino.

Last year we

were in a strong El Nino with SST anomalies peaked in November-December last

year.

The primary

metric used by NOAA to gage the strength of an ENSO event is the

three-month-average temperature of the central tropical Pacific Ocean,

specifically in the Nino-3.4 region.

The

temperature anomaly—the difference from the long-term average, where long-term

is currently 1991–2020—in this region is called the Oceanic Nino Index (ONI).

We use a three-month average because ENSO is a seasonal phenomenon, meaning it

persists for at least several months.

The

threshold is further broken down into Weak (with a 0.5 to 0.9 SST anomaly),

Moderate (1.0 to 1.4), Strong (1.5 to 1.9) and Very Strong (≥ 2.0) events.

While we

don’t have official strength definitions, but, unofficially, an ONI anomaly of

1.5 °C or warmer is considered a strong El Nino. Last year the ONI peaked at

2.0 °C which would indicate a very strong El Nino.

Since

November-December last year, SST have dropped. Some areas in the equatorial

Pacific are already showing up cooler, as upwelling is bringing cooler water to

the surface. We’re quickly heading toward neutral. We’re most likely going to

become neutral sometime next month or in May. After that we should quickly move

into La Nina. The chances are growing for a La Nina to develop by summer and

hurricane season 2024.

The colder

subsurface water temperatures are just beneath the surface. Looking back at the

equatorial Pacific Nino regions, we can see region 1+2 off the South American

Coast is already showing much cooler SST.

Typically,

during La Nina hurricane seasons, the Atlantic Basin sees a more active season

due to less wind shear and trade winds and more instability.

During a La

Nina year that follows a strong El Nino like the one that is happening in 2024,

the tracks of tropical cyclones tend to be more active in the Caribbean and GOM.

The El Nino

events in the record (starting in 1950) with the largest Oceanic Nino Index

values are 1972–73 (2.1 °C), 1982–83 (2.2 °C), 1997–98 (2.4 °C), and 2015–16 (2.6 °C). 1987-1988 El Nino reached (1.7 °C). 2009-2010

(1.5 °C) These seasons were all followed by a La Nina.

Possible

Analogues…

La Nina

seasons following a strong El Nino

1973, 1983,1988,1995,1998,

2010 and 2016

Saharan air

layer (SAL) could be an inhibiting factor, especially during the first part of

the season. As I’ve said in the past, the SAL is a layer of hot dry that can

contain Saharan dust, blown off of Africa and out over the Atlantic.

SAL creates

atmospheric parameters that suppress tropical cyclone formation and

intensification. Last season featured less than average SAL over the Atlantic. If

that is again the case this year; it would increase the odds for an active

season.

The

Bermuda/Azores High (BAH) is a large area of high pressure that develops over

the subtropical Atlantic Ocean. It exerts a lot of influence on the track of

tropical systems.

The location

and strength of the BAH will also be important. As this will determine how far west the TC can

track. If the BAH is weak and farther east TCs will have a greater chance to

curve north up into the Atlantic. On the other hand, if the BAH is strong

farther west, there will be a greater opportunity of the TCs to make in into

the western Atlantic along with the Caribbean and GOM.

AccuWeather is calling for 20-25 named storms, with 8 to 12 becoming hurricanes, 4 to 7 of those becoming major hurricanes (Category 3 or above with at least winds of at least 111 mph). They are predicting 4 to 6 U.S. landfalling TCs. They say the seasonal Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) will be 175-225.

Colorado State University (CSI) is calling for 23 named storms, 11 becoming hurricanes, 5 of those becoming major hurricanes.

WeatherBELL Analytics

says the season will have 25-30 named storms, with 14 to 16 becoming hurricanes.

Of these they are calling for 6 to 8 major hurricanes, with a seasonal ACE of 200

to 240.

Tropical

Storm Risk (TSR) calls for 20 named storms, 9 of these becoming hurricanes and

4 of these to become major hurricanes, with a seasonal ACE of 160.

All of these

have one thing in common; they are all calling for a very active and possibly

explosive hurricane season.

Based on the

SST temperature profiles, I think 2024 should be similar to seasons like 2020, 2017,

2011, 2010, 2008, 2005 and 1995.

While there

is no guarantee that an active season results in several U.S. landfalling TCs.

It does increase the odds.

The data

shows that the risk for hurricanes making landfall, are almost double when the

Atlantic is warm vs when it is cool. The data also shows the risk for

landfalling hurricanes is almost two and a half times greater during La Nina

seasons vs El Nino seasons.

We also have

those well above average SST in the Northeast Pacific. This favors a pattern that

could be very similar to what we had in 2005, 2007 and 2020. Those years saw several

U.S. Tropical Cyclone landfalls.

With the

super warm water in the Atlantic there is a greater risk for TCs to rapidly

strengthen. When you add in the increased risk for landfalling systems, the

idea of rapid intensification is something to worry about.

In part one,

I said the eastern Gulf Coast, Florida and the Carolinas are at an above

average risk for direct impacts. With a slightly less risk for the Texas Coast,

Middle Atlantic and New England seeing possible landfall TC risk. That still seems to be true. The Caribbean is

also going to be at a heightened risk.

The U.S. will likely see multiple landfalling tropical cyclones.

I will be

releasing part three in May.