Everyone's

Atlantic hurricane forecast for 2013

were calling for above normal to way above normal activity.

For

the 2013 hurricane season NOAA’s Atlantic Hurricane Season

Outlook predicted the following:

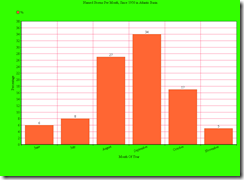

70 percent likelihood of 13 to 20 named storms (winds of 39 mph or higher)

7 to 11 would become hurricanes (winds of 74 mph or higher)

3-6 major hurricanes (Category 3,4, or 5: winds of 111 mph or higher)

Respected veteran

hurricane scientist Bill Gray and his team at Colorado State University

called for 18 named

storms during the hurricane season, between June 1 and Nov. 30.

Eight of those are expected

to become hurricanes.

Three of those are

expected to become major hurricanes (Saffir / Simpson category 3-4-5) with

sustained winds of 111 mph or greater.

Believe it or not, this

is a slight reduction from the early April and early June forecasts when the

team called for 18 named storms, nine hurricanes and four major hurricanes.

I said, I was using the weather patterns of past years and decades, along with other factors to make my tropical outlook.

Since 1950 the years 1952,1996, 2007, and 2008 had very similar oceanic and atmospheric characteristics to those forecasted for this years tropical season.

My forecast was this:

"This season will be quite active with 13-18 named systems, with 8-10 becoming hurricanes, four or five (perhaps more) of which will make landfall somewhere in the U.S. Also, I feel 2-4 of these will strike or impact the Northeast and northern Mid Atlantic states. Of the 13-18 named storms 3-4 will be major hurricanes. Once we get toward the end of July and onward I think the season will become quite active. "

So far, named storms in

the Atlantic basin hasn't lived up to mine or anyone's expectations , Jerry makes our 10th named

storm for the season... this is above average

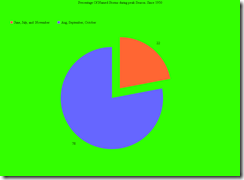

But, we've only had two

hurricanes so far this season....Humberto briefly became a hurricane Sept. 11, a

Category 1 with winds under 95 mph. It was named a hurricane just three hours

before it would have been the latest first hurricane since the satellite era. The

other hurricane was Ingrid Which momentarily became a Category 1 before

landfall in Mexico.

So while activity is

above normal, the intensity of these tropical cyclones hasn't come any way near

what was forecasted.

Tracks for the named systems for the 2013 season

With records going

back to 1851, Dennis Feltgen, a spokesman for the U.S. National Hurricane

Center, said there had been only 17 years when the first Atlantic hurricane

formed after Sept. 4.

Feltgen said "The all-time record

was set in 1905, when the first hurricane materialized on Oct. 8".

In an average season the seasons first hurricane shows up by Aug. 10, with the

second hurricane quick on its heals on

Aug. 28 and the first major hurricane normally forms by Sept. 4.

As I've said in post and on my Facebook page, since the dawn of the satellite

era, started in 1967. Hurricane Gustav

set the modern record on September 11, 2002 as the latest date for the first

hurricane to arrive.

The Accumulated

Cyclone Energy index -- a rating system that compares the intensity of storm

seasons -- would normally be around 55 for the Atlantic. It's now a paltry 16.

Globally the rating is a stunning 255, roughly half of what we should see this

time of year.

normally when an ocean basin

kicks up a fuss on one part of the globe, usually another ocean basin is quiet.

Nature tends to balance itself that way. This year, according to the ratings,

storm activity in all the world's ocean basins is below normal.

So what is going on?

We had a very

strong Bermuda high for most of the

Summer...This helped suppresses tropical

cyclone development.

Most of the season has

seen a very stable atmosphere over the tropical Atlantic.

In a normal El Nino

year the tropical water in the Pacific west of South America are warmer than

normal, this leads to a lot of wind shear across the Caribbean , which

suppresses Tropical Cyclones

Now while, this has

not been a El Nino year, the waters in the tropical Pacific have been above

normal, perhaps this has something to do with all the wind shear we've been

seeing.

The location of the

Jet Stream for a good part of the Summer had been farther south than average

Making it wet in both

the Northeast and Southeast along the Eastern Seaboard... this could also be

helping in creating shear......

There also has been an

ongoing drought in northeast Brazil.

These could have had a major role in the placement of the Tropical Upper Tropspheric Trough

(TUTT) for the 2013 season.

TUTT is an upper level

trough that helps with convection in the tropics

It is normal to see it over the Atlantic and

Pacific for part of the year.

The location of the

TUTT is key as to if it will aid or hinder tropical cyclone development

TUTT helps support

vertical wind shear.. Normally south of the TUTT you have strong westerly wind

shear ...Tropical cyclones don't like environments like that.....But north of the

TUTT the wind shear is normally less...so tropical cyclones that form there

have a better chance for development.

The TUTT isn't always

bad, there are times when they can help build better outflow of the storms

center.....there have been times where the TUTT became cut off and became a

tropical cyclone.

TUTT over the Atlantic

basin first appears in June, strengthens in July and August, and then weakens

in September and October. During August (the start of prime time for Atlantic

tropical cyclones), the TUTT tilts from southwest to northeast, spanning from

Cuba to roughly latitude 35 degrees North at around 250mb

This season there were

several times where the placement of the TUTT caused strong west and southwest winds aloft which

helped suppress tropical cyclone development.

The SAL layer... I

feel this was the biggest factor this year....

tropical storms and hurricanes develop and intensify by

feeding off warm, rising, moist air. But, the Atlantic's hurricane breeding

ground has been dominated by dry, sinking air for much of the summer....normally you don't see these huge

dust storms coming off the African Coast during the hurricane season...... The

High pressure in the Atlantic was too far north... if it had been farther south it would have forced the air to

come off the Congo instead of the Sahara Desert ...The Congo is all rainforest, therefore it has a

lot more moisture......this would have been much more conductive for tropical cyclone development.

I don't like to see death and destruction, so a slow season is a good thing. one thing I want to mention is the almost always present high pressure over the eastern

part of the Country has helped protect the Northeast from the few storms that

did form.

From the hurricane climatology standpoint, storms ordinary

form closer to the U.S. coast later in the season, like Hurricane Sandy last

year.”

Looking back at the records, in the past 60 years there have

been three seasons with no named storms at any time from September 20th through

September 26th: 1991, 1997 and 2009. All of these were El Nino seasons,

however, there have been other El Nino seasons during this 60 year period -

including 2002 and 2004 which were active seasons. In 1993, a slightly positive

ENSO Neutral year, there were no named storms after September 21st. So far,

2013 is a slightly negative to an Neutral ENSO season.

Looking at the Teleconnections, most of the same atmospheric

conditions that have so far interfered with tropical cyclone development could

persist into November.

Looking at everything, I don’t see any significant changes

for the Atlantic Basin for the rest of the 2013 hurricane season. But we will see.